Critically ill patients treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) often experience imbalances in their gut microbiome due to the illness and treatment. This dysbiosis is associated with issues like delirium, septic encephalopathy, cognitive impairments, and behavioural disorders. Additionally, dysbiosis can contribute to post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), leading to lasting physical, cognitive, and mental health challenges after critical illness.1

The human microbiome, comprising a diverse array of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, plays a vital role in various aspects of health. The gut microbiome, mainly consisting of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites influence not only the metabolic and immune systems, but also nervous system activity.1

Role of gut health in different organ systems

The gut microbiome has a significant influence on lung immunity through the gut-lung axis. Dysbiosis (disruption of the microbiome) can contribute to respiratory issues, including refractory asthma and increased susceptibility to viral and community-spread pneumonia.1

Imbalances in the gut-heart axis can lead to inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, and the translocation of harmful substances, potentially resulting in cardiovascular complications and worsened outcomes.1

The gut-kidney axis is associated with microbial imbalances resulting in kidney-related diseases such as including type 2 diabetes. Overgrowth of pathogenic microbes can lead to severe conditions like sepsis and peritonitis.1

Disturbances in the gut-muscle axis have been associated with muscle weakness, affecting the recovery of survivors of critical illness.1

ICU therapies and gut dysbiosis

Critical illness and therapies used in the ICU can cause the loss of commensal micro-organisms, leading to gut dysbiosis. Antibiotics, while beneficial for infections, can reduce microbial diversity and contribute to antibiotic resistance, impacting the gut microbiome.1

What is PICS?

The term PICS was coined in 2010, to describe new and persistent declines in physical, cognitive, and mental health functioning (excluding traumatic brain injury or cerebrovascular accident) that follow ICU stay.1,2

A study by Marra et al found that 64% and 56% of survivors had one or more PICS impairments after three and 12 months, respectively. Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder are also prevalent among ICU survivors.2,3

A review by Ong et al revealed functional impairment rates of up to 36% at discharge, 26% at six months, and 19% at two years among paediatric ICU survivors.4

The ICU experience, marked by isolation, fear, and dehumanisation, contributes to psychiatric sequelae. Risk factors include a personal history of psychiatric illness, female gender, younger age, sedative exposure, and limited recall of the ICU experience. Hypoglycaemia and hypoxia increase the risk of cognitive dysfunction and depressive symptoms.2

PICS also impact family members (PICS-f) who experience subsequent adverse mental health outcomes, the most common of which are sleep deprivation, anxiety, depression, and complicated grief. Up to 75% of family members of ICU patients develop symptoms consistent with PICS-f, with >30% requiring psychiatric medication for management.2

Risk factors for PICS-f include female gender, younger age, lower education, and a history of mental health disorders. Parents of critically ill children are particularly vulnerable.2

What causes PICS?

PICS is caused by ICU-acquired muscle weakness (ICUAW), which involves a symmetrical decline in skeletal muscle strength, leading to difficulties in ventilator weaning, speech, swallowing, and limb weakness. Subcategories include muscle deconditioning, critical illness polyneuropathy, and critical illness myopathy, coexisting as critical illness neuromyopathy.2

Mechanical ventilation induces rapid respiratory musculature wasting, exacerbated by opiate and sedative administration, leading to disuse-mediated atrophy. Neuromuscular blockers may contribute to weakness, persisting after cessation, similar to myopathy observed in denervation injuries. Prolonged bed rest and immobilisation also weaken limb and trunk muscles.2

ICUAW involves not only disuse-induced skeletal muscle atrophy but also inflammatory mediators, electrolyte imbalances, endocrine dysfunction, and poor nutrition, impairing protein synthesis and promoting proteolysis. Vitamin D deficiency, prevalent in hospitalised patients, especially those with darker skin tones, contributes to skeletal muscle weakness. These factors, along with microvascular ischaemia, underlie the neuropathic components of ICUAW.2

Cognitive impairment in PICS persists post-ICU discharge, with deficits in memory, processing speed, and attention. Risk factors include hyper- or hypoglycaemia, pre-existing cognitive deficits, and prolonged hypoxia during the ICU period. ICU delirium correlates with subsequent cognitive deficits.2

Can PICS be prevented?

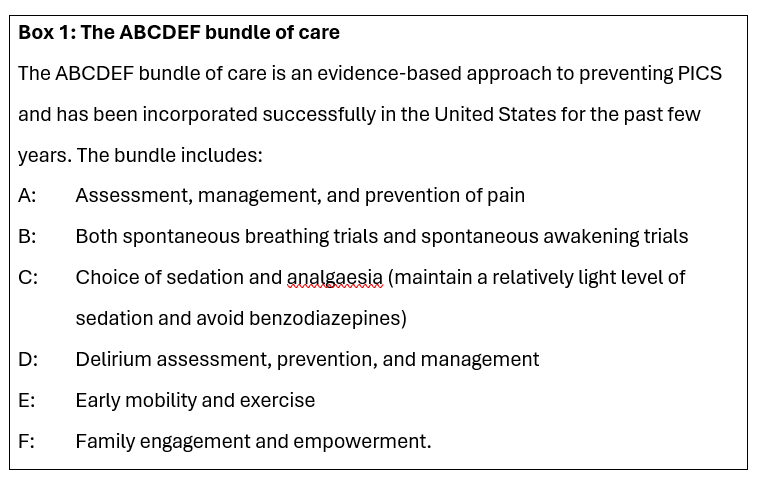

Smith et al acknowledge that limited resources is a barrier to the implementation of screening patients for PICS. However, state the authors, the implementation of the ABCDEF bundle of care (see Figure 1) in the ICU setting is relatively simple and effective.2

Some researchers have also proposed implementing a functional reconciliation test to compare a patient's current functional status with their pre-ICU condition.2

This process should encompass evaluations of activities of daily living (ADLs), exercise tolerance, mood, and cognitive indicators, including the ability to return to work or manage personal affairs.2

A comprehensive physical examination, involving the assessment of vital signs, is essential when evaluating a patient post-recovery from critical illness, given the potential precariousness of their medical condition.2

Furthermore, the patient's overall appearance can offer insights into their functional and health status. For instance, bitemporal wasting (the loss or atrophy of muscle tissue in the temporal region on both sides of the head) may signal sarcopenia, while poor hygiene may indicate limitations in ADL independence.2

Assessment of the patient's affect and body language can also potentially reveal underlying mental health issues. Special attention to the neurologic exam is crucial to identify signs of myopathy or neuropathy, considering the prevalence of ICUAW.2

A brief cognitive assessment, like the mini-mental status exam, should also be conducted, and if deficits are apparent, more comprehensive neurocognitive testing should follow.2

Furthermore, debriefing patients and their families at the time of ICU or hospital discharge to make them aware of the signs of PIC can contribute meaningful to the prevention of PICS.2

Can restoring the gut microbiome affect outcomes?

The study by Sung et al show that the use of probiotic supplementation to modulate the microbiome holds promise in restoring the gut microbiome in critically ill patients. Probiotics have been shown to curb the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and to fortify immune system responsiveness.1

According to Sung et al, including probiotic fermented foods in the diet can increase microbiome diversity and reduce inflammatory markers. For example, yogurt with the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis demonstrated superior preservation of the colon's commensal bacterial community compared to a placebo, especially post-antibiotic therapy.1

After discontinuing antibiotics, the probiotic group's acetate levels rebounded and returned to baseline by day 30, while the control group's levels remained suppressed.1

The incorporation of fermented foods into the diet has been linked to an enhanced immune response and various positive health outcomes. Interventional studies involving fermented tea, sauerkraut, fermented plant extract, kimchi, and fermented soybean milk have shown increased presence of gut bacteria associated with health benefits. Additionally, the dietary inclusion of fermented products has been associated with positive changes in cerebral activity and demonstrates a broader neuroprotective influence.1

Conclusion

The relationship between critical illness, the gut microbiome, and subsequent PICS poses significant challenges to patient outcomes. Dysbiosis induced by critical illness and ICU therapies can lead to a cascade of complications affecting various organ systems. PICS, encompassing physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments, is a serious consequence of ICU ICUAW. The implementation of the ABCDEF bundle of care in the ICU setting and the proposed functional reconciliation test offer practical strategies. These approaches involve comprehensive evaluations of patient functionality, encompassing daily activities, exercise tolerance, mood, and cognitive indicators. Recognising risk factors and debriefing patients and families at discharge are crucial steps in preventing and addressing PICS and its associated mental health sequelae.

References

- Sung J, Rajendraprasad SS, Philbrick KL, et al. The human gut microbiome in critical illness: disruptions, consequences, and therapeutic frontiers. Journal of Critical Care, 2024.

- Smith S, Rahman O. Postintensive Care Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558964/

- Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Co-Occurrence of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome Problems Among 406 Survivors of Critical Illness. Crit Care Med,

- Ong C, Lee JH, Leow MK, Puthucheary ZA. Functional Outcomes and Physical Impairments in Pediatric Critical Care Survivors: A Scoping Review. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2016